A Nobel Peace Prize-winning bishop alleged to have abused teenaged boys during the 1990s was sanctioned by the Vatican, which limited his movements and prohibited him from contact with minors or with his home country of East Timor. Meanwhile in Yakima, Washington, after a whistleblower raised concerns about the previous bishop’s handling of sexual abuse allegations, the now-retired bishop received a formal reprimand from the Vatican.

Though the details of these two cases differ, what they share in common is that the consequences to the church leader under investigation — and even the fact of the investigation itself — were kept secret. That is, until news media shared the truth.

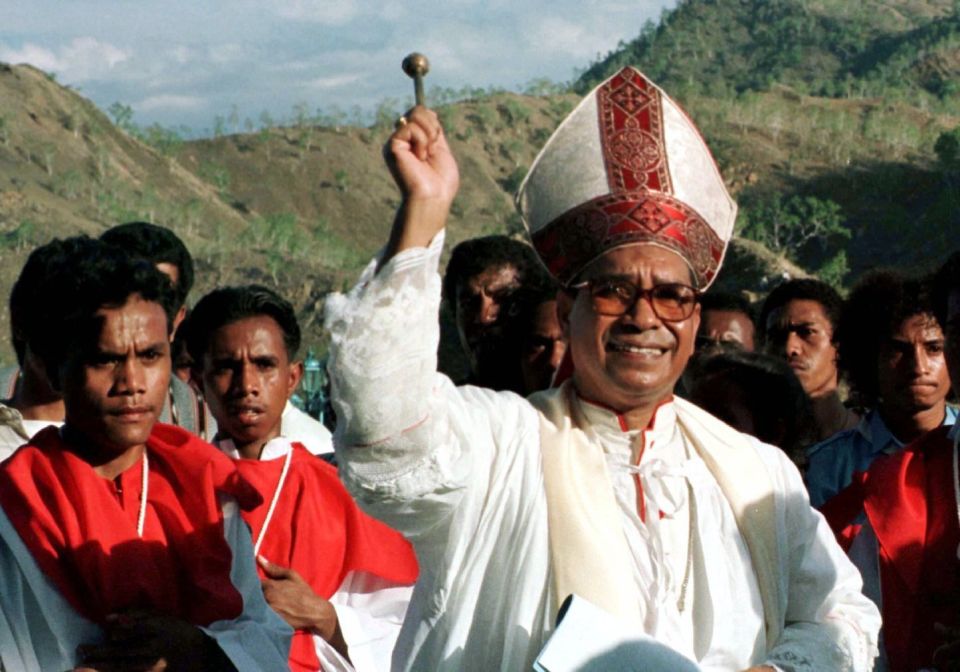

In the case of Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo, who shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996 with current East Timor President José Ramos-Horta for their nonviolent resistance to Indonesia’s occupation, the Dutch publication De Groene Amsterdammer last week (Sept. 28) published the stories of two alleged victims, who said Belo gave them money after sexual abuse. The paper also reported that other victims were afraid to come forward.

Only then did a Vatican spokesperson reveal that the then-Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith imposed disciplinary restrictions on Belo in 2020, after having received allegations in 2019. In November 2021, these measures were modified and reinforced. Both times the bishop formally accepted the restrictions.

Similarly, in Yakima, whistleblower Robert Fontana, a former diocesan director of evangelization who had requested an investigation into Bishop Carlos Sevilla, was told about the « reproof » of the prelate during a private meeting in which Fontana says he was not allowed to see the document from the Vatican or take notes. The Yakima Herald-Republic first reported this story, and NCR’s Katie Collins Scott recently took an in-depth look at this case.

Fontana alleges that Sevilla, who led the central Washington diocese from 1996 until retiring in 2011, poorly handled numerous abuse allegations, including a case involving possible abuse of altar servers and another involving a priest who allegedly downloaded child pornography. Sevilla contests the allegations.

Both the Belo and Sevilla cases were handled by the Vatican under the norms of Vos Estis Lux Mundi (« You Are the Light of the World »), Pope Francis’ system to evaluate reports of abuse or cover-up by bishops issued in the wake of the exposure of abuse by former cardinal Theodore McCarrick in 2019.

At the time, NCR’s editorial expressed concern about the system’s reliance on self-policing, since investigations are the responsibility of a brother bishop, rather than review boards that include laypeople (although laypeople can be consulted in the investigations). Reactions from others in the church mirrored those concerns, saying Vos Estis was a necessary, though not final step.

A year into Vos Estis, an NCR report raised questions about whether the process had an appropriate level of transparency about bishops who were being investigated. A year later, another NCR report found similar criticisms.

Vos Estis was initially adopted for a three-year period « ad experimentum, » which ended June 1. There has been no announcement since then, but the assumption is that the law will become permanent. It’s possible the pandemic has delayed any announcement.

As the experimental period ended, Anne Barrett Doyle of BishopAccountability.org warned that Vos Estis wasn’t working: « Too few bishops have been found guilty, they’ve been punished too lightly, and next to no information about their misdeeds has been disclosed. »

Doyle suggested multiple changes, but the one that seems to be a no-brainer is the need for less secrecy and more transparency. Under Vos Estis, there is no requirement that the Vatican inform the faithful about an investigation or its conclusions. Likewise, victims or whistleblowers are not guaranteed communication.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The argument against more transparency is that public accusations could hurt the reputations of bishops who are later exonerated. Others argue for the need for confidentiality in ongoing legal processes.

But surely there is some threshold at which the people of God have the right to know: just as in our legal system, in which grand jury proceedings are secret, but once credible evidence moves toward an indictment, the rest of the proceedings—and their conclusions—are public.

As the Belo case proves, many allegations eventually become public anyway, at which point the church appears defensive and unwilling to trust its people with the truth in the first place.

But this is not about public relations for the church. More transparency is the only way to heal after decades of this scourge of sex abuse and cover-up. Now is the time for more of it.