Last July was the hottest month ever measured, and in late June my friends and I were drenched in sweat. The apocalyptic weather was miserable, but nothing could damper our excitement to see boygenius live at Centennial Park in Nashville, where from our seats in the grass we could see a full scale replica of the Greek Parthenon.

The replica was built for the 1897 Centennial Exposition primarily because of Nashville’s nickname, « The Athens of the South. » It has the grandiosity of a temple, with massive columns that bear the weight of its ornate roof, meticulously designed with the stories of Greek myths. But get too close, and you’ll notice it’s made of pebbles and concrete, hardly marble. It reminds me of my great-grandma’s driveway in Mississippi. This is, after all, not Greece. It’s a stop on the « Sites of Nashville » bus tour. Still, it was an impressive backdrop to one of the best rock shows I’ve ever seen.

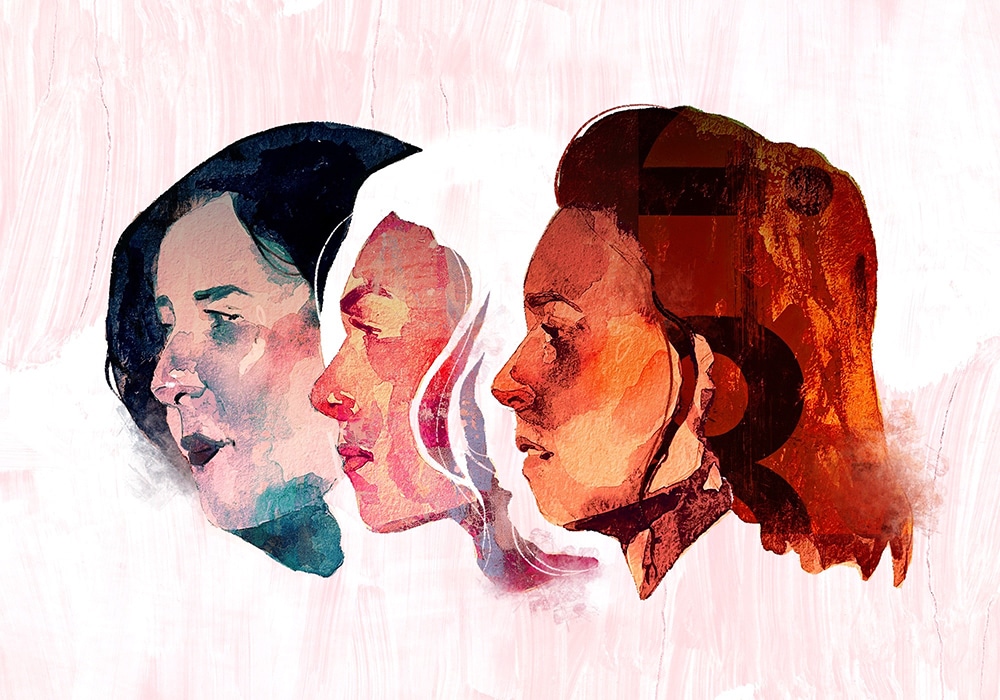

Boygenius is a supergroup composed of three indie rockers: Phoebe Bridgers, Julien Baker, and Lucy Dacus. The band had a remarkable year; they released their debut album, aptly titled « The Record », graced the cover of Rolling Stone, gave an iconic Coachella performance and took home three Grammy awards for best rock song, best rock performance and best alternative music album. Each artist has incredible discographies in her own right, but together their synergy is magnetic.

« What are they wearing? » I asked my friends, squinting to make it out. « Are they in drag? » Sure enough, boygenius took the stage to perform that night costumed in drag as a protest against Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee’s « drag ban, » a bill he had signed that March, that would prohibit drag performances from happening on any public property in the state. (In early June a judge ruled the law unconstitutional.) In a bizarre twist, a photo of Bill Lee himself dressed as a woman circulated earlier that year, around the time he signed the legislation.

Maybe it was the heat cooking my brain, or that despite a recent school shooting, Gov. Lee could only talk about how drag queens were the most dangerous thing facing Tennessee’s children; or maybe it was that the Nashville Parthenon felt like a portrait of our country, an empire that daily feels more like a facade. A roadside attraction. Whatever was to blame, I found myself overcome with the sense that we are all languishing. We’re living at the end of something, it seems; the end of an empire, capitalism or maybe the planet itself.

This nagging feeling holds a prominent place in boygenius’ music, particularly their newest album.

« The Record » is deeply honest, not just about the state of the world but also about the complicated feelings and relationships young people are figuring out while navigating the state of the world. The empire might crumble, but we still have breakups; we still have to find peace with the decisions we’ve made and discover who we were meant to be.

All of that coalesces into an album that feels like an intimate conversation between lifelong friends. Even the flow of the album models a conversation. At times, Bridgers, Baker or Dacus will hold an entire song, illustrating the details of what they’ve gone through for the others. On other tracks, the vocalists will each take their own verses, bouncing off each other and adding to the conversation.

In « Satanist, » the three wonder if they were to take their beliefs to their extreme ends, would their friends still be around? Each imagines a caricature of themselves living just past what people in their lives might be comfortable with. It’s a great, fun rock song. But just like those kinds of conversations, the song ends in quiet harmony, agreeing that differences in belief over time can grow into a « seismic drift » impossible to come back from and that the three are worried that the world that is radicalizing them more and more each day will isolate them. There’s that feeling again.

To see boygenius live is electric. The three bounce around the stage, hugging each other and rolling around. They’re unsupervised kids playing rock stars in their garage. Their genuine love for each other and the music is palpable. There’s a sense that Lucy Dacus is speaking directly to her bandmates in « True Blue » when she sings, « It feels good to be known so well/ I can’t hide from you like I hide from myself. »

Trying to explain friendship is like trying to explain a joke; it just ruins it. « The Record » has that inexplicable quality. Boygenius has created an album that will go down as one of the best rock albums of our time — with the Grammys to prove it — but on the other hand, boygenius is a group of three friends who thought it would be fun to start a band, go on tour and lose their minds on stage together every night.

It’s that balance between existentialism and revelry that boygenius does so well. The Swiss Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz once said, « It’s easy to be a naive idealist. It’s easy to be a cynical realist. It’s quite another thing to have no illusions and still hold the inner flame. »

If the impending ecological disaster, the ever-revealing cheapness of our temples and institutions or the absurdity of our government officials is more than you can bear, boygenius gets it. But in all of that, boygenius reminds us we still have a life to live. Even if the world is ending, you should still start that band, go on that road trip, find the people who get you — and love them.