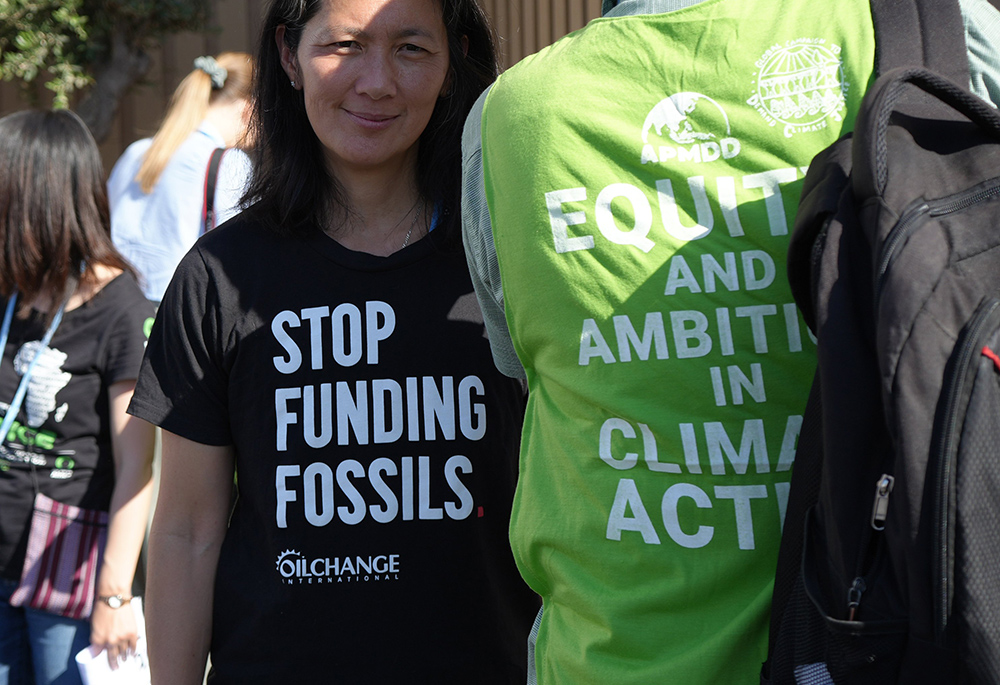

Despite a few successes — like the establishment of a loss and damages fund — the latest United Nations international conference on climate change (COP27) fell short by failing to name the main source of our global problem: the burning of fossil fuels.

Globally, greenhouse gas emissions are still rising, and most nations are not on track to reduce their emissions at the necessary pace to avert irreversible climate impacts. New fossil fuel projects are being planned or developed across the globe. Keeping the Paris Agreement objective of 1.5°C maximum planetary warming alive seems like an already lost battle.

Religious institutions were present at the November climate summit in Sharm el-Shiekh, Egypt, to lend their moral influence to climate conversations. But one of their most significant contributions to the cause is more tangible than morality, albeit an avenue of often untapped potential: church finances.

Religions worldwide are incarnated into millions of institutions — churches, temples, congregations, schools, health services and more. These institutions own and manage large plots of land, numerous buildings and significant financial assets. In addition to their spiritual and moral influences, religious institutions’ possessions give them great temporal power.

Over the last six years, hundreds of Catholic institutions have publicly committed to divesting from fossil fuels, and thereby aligned their investment policies with the social teachings of the church on care for our common home. By divesting, Catholic institutions raise a prophetic voice, echoing Pope Francis in his 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’, « We know that technology based on the use of highly polluting fossil fuels — especially coal, but also oil and, to a lesser degree, gas — needs to be progressively replaced without delay. »

Yet, the Catholic world is vast, and there are still many voices missing from divestment announcements, despite the Vatican’s clear guidelines. I suspect there are a few reasons for this, among them disconnection, discomfort, confusion and complexity.

Finance is often seen as a technical issue outside the scope of moral and pastoral issues, therefore finance committees and staff are isolated from the work of their counterparts in ministries of justice, peace and creation care. But as Francis says in Laudato Si’, « Everything is interconnected. » Just as Catholic values should influence investing, finance professionals should share their industry knowledge by translating into comprehensible language what are the options on the table. Finance is a means to many ends, not only a way to earn more money.

Many institutions have become used to steadiness in high return and low risk investments. The complexification and commodification of financial assets hides our responsibility as owners or lenders. Some congregations or institutions rely on wealth accumulated over time to take care of elderly members of their communities or to implement projects they have planned over the years. The diversity of financial vehicles must not prevent from having discussions on why and how the wealth accumulated over time is to serve church missions. This is exactly what Mensuram Bonam, the recent text of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences, tells us.

The extent of the changes needed is complex and multifaceted. We need some imagination to prepare for the future — to cut emission by half in less than eight years (what is required by the Paris Agreement) looks more like the rapid conversion to war economies during World War II than the gradual transition into the industrial era two centuries ago. This speedy transition can only succeed with total engagement from all actors and strong stewardship of public authorities. Investing 5% of assets in impact investing isn’t sufficient. Decisions to fully divest from fossil fuels and invest in climate solutions show the way forward. Holding shares in, and thus profiting from, fossil fuels means not taking the Paris Agreement or church teaching seriously.

Fossil fuel-related investments’ market values are overestimated and accumulated money is likely to disappear if it’s invested in fossil fuel-related assets, what Carbon Tracker has dubbed « stranded assets. » Financial predictions have been unable to integrate the extent of the damages climate change will inflict on us. For example, only some insurers realize they cannot insure large infrastructures at risk because of more frequent extreme weather events. As the impacts of climate change worsen, our societies and economies are going to change dramatically. « We don’t need an army of actuaries to tell us that the catastrophic impacts of climate change will be felt beyond the traditional horizons of most actors — imposing a cost on future generations that the current generation has no direct incentive to fix, » said Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England at the time.

This poses challenges for the business model of many Catholic institutions. Those who work in finance departments can no longer manage assets according to prudential rules based on the economy of the past, they must consider the economy needed for the future. We cannot separate questions of finance from political and moral questions. That is why the Laudato Si’ Movement encourages Catholic institutions not only to divest from fossil fuels, but also to endorse a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty. Those are two sides of the same coin.

The church has sustained itself over time through prudence, but also through prophetic stances, boldness and a spirit of service. It may be difficult for Catholics to put Laudato Si’ and the social teachings of the church into action. But identifying specific challenges can help us overcome them, and help the Catholic Church to raise a prophetic voice and induce dramatic change through the reorientation of its finances.