A couple of weeks ago, a conservative Catholic magazine named me the second-worst Jesuit in the United States — No. 1 was my friend Fr. Jim Martin.

I was disappointed in the article: I should have been No. 1. After all, I hired and mentored Jim when I was editor of the Jesuit news and opinion journal America, but this is clearly a case of the student outshining his teacher. I write about the Vatican; Jim influences Vatican policy.

My conservative critics would be surprised to learn that, as a high school student and young seminarian, at a time when everyone around me was enamored with John Kennedy, I was a Goldwater Republican. I even had a subscription to the National Review.

When I entered the Jesuit seminary at Los Gatos, California, in 1962, just prior to Vatican II, I was very comfortable with the church as it was in the 1950s, when the Jesuits were described as the pope’s Marines.

What happened to change me?

In our extremely conservative novitiate, the director of novices imbued us with a traditional spirituality in which obedience to superiors is considered a response to the voice of God. But he also taught us not to be judgmental. Thinking you are better than others is a sign of pride and arrogance, he said, especially if you are passing judgment on a person’s thoughts and motivations, which you cannot see.

This fundamental teaching, plus my natural shyness, stuck with me when the Second Vatican Council seemed to change everything. It kept me from condemning everyone who did not follow the rules. (Only when I became an editorial writer, years later, did I break out of my shell.)

For the first four years of my seminary training, however, we were not even told that the Second Vatican Council was taking place. We had no radio, television or newspapers during this time.

Somehow, I learned about the council and asked the seminary rector if I and a friend (another Republican) could have a copy of the council documents. After much debate among the faculty, the two of us were given the documents; the other seminarians didn’t get them for another couple of months.

Ultimately, it was the council that liberated me from traditionalism. My training in traditional obedience made me receptive to the council teachings, which, after all, came from the pope and the hierarchy. If this is what the pope wanted, then as a good Jesuit, I should salute and follow. Sadly, today’s conservatives do not do this when Pope Francis points the way.

The council documents opened my eyes to a greater understanding of the liturgy, the role of the church in the world, social justice, ecumenism and interreligious relations. My understanding of the council was later enriched by Jesuit Fr. John O’Malley’s What Happened at Vatican II.

As a conservative, I also approached the Scriptures and the U.S. Constitution in a literal way. In grammar school, we had a textbook with diagrams showing how Jonah could survive inside a whale.

During my third year at Los Gatos, I discovered the Paulist Bible series that devoted a pamphlet to each book of the Old Testament and the Collegeville series on the New Testament. This introduced me to contemporary Scripture scholarship, which uses literary criticism and history to understand what the author was trying to tell his audience.

I would continue this study when my studies in theology introduced me to Sulpician Fr. Raymond Brown and other scholars. My understanding of the parables was forever changed by Jesuit Fr. John Donahue’s The Gospel in Parable. Today, I always consult the Jerome Biblical Commentary before writing a homily.

Advertisement

When I was sent to St. Louis University to study philosophy in 1966, all hell was breaking loose in the church and in America. At this time, ignorant and confused church leaders made it difficult to see the voice of God in superiors.

Those in charge of the church did not know how to implement the council reforms; liturgical change came unexplained. As an obedient Jesuit, I saluted and went along and eventually loved it. I was not threatened by the changes because at Los Gatos I had read The Mass of the Roman Rite, the magisterial history of the liturgy by Jesuit Fr. Joseph Jungmann. No one can read this book without concluding that the only constant in the history of the Mass is change.

My political transformation also began in St. Louis. I took a course on constitutional development and concluded that the U.S. Constitution is what five of nine Supreme Court justices say it is.

The Vietnam War, which I supported, was also going on. I changed my view after reading Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled by Joseph Buttinger, which showed the United States was making all the same mistakes the French had made earlier. And although Catholics suffered after the war, the predicted bloodbath did not take place. Today, Vietnamese Catholics can practice their faith as long as they do not challenge the ruling party.

After ordination, my experience as a tax reform lobbyist with the nonprofit Taxation With Representation soured me on Republicans and business leaders, who decry government spending and interference in the marketplace but line up at the government trough for tax subsidies and loopholes. We attacked these subsidies as interference with the market. Our proposal was to eliminate loopholes and use the money to cut the tax rates for everyone. They hated us for exposing their hypocrisy.

My conservative instincts were still operating when I was editor of America and the Bush administration warned of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. My liberal colleagues wanted us to condemn the invasion, but I worried about looking foolish if these weapons were found. For me, the deciding factor was opposition to the invasion by Pope John Paul II. If I was wrong, at least I would have the pope for company.

Another book that transformed my theological views was Contraception by John T. Noonan, which told the history of the church’s teaching on contraception. I remember throwing the book at the wall after reading the section describing how the Irish confessional manuals had a bigger penance for contraception than for rape, because rape was a « natural » act. Game over.

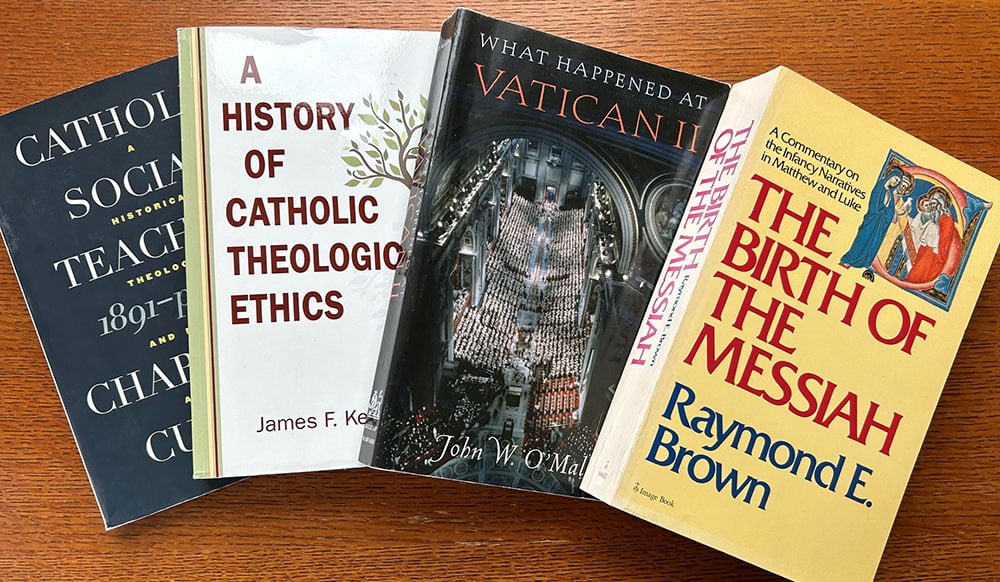

To seminarians and other Catholic conservatives, I recommend the books that changed my life: The Mass of the Roman Rite, anything by Brown and other Scripture scholars, Contraception and What Happened at Vatican II. Other favorites include The Church by Fr. Hans Küng, Catholic Social Teaching 1891-Present by Charles Curran and She Who Is by St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson. Today, I am reading A History of Catholic Theological Ethics by Jesuit Fr. James Keenan.

Most of these books are histories, which I see as an antidote to ideological thinking. Ideologies are systems by which you ignore data in order to arrive at an absolutely certain opinion.

For more systematic theology, you cannot go wrong with the writings of Karl Rahner, Edward Schillebeeckx and Bernard Lonergan, although I confess I found them tough going.

There are lots of great books in theology. These changed my life. I hope the fact that they are being recommended by the second-worst Jesuit in the United States does not mean that they will now be banned from seminary libraries.