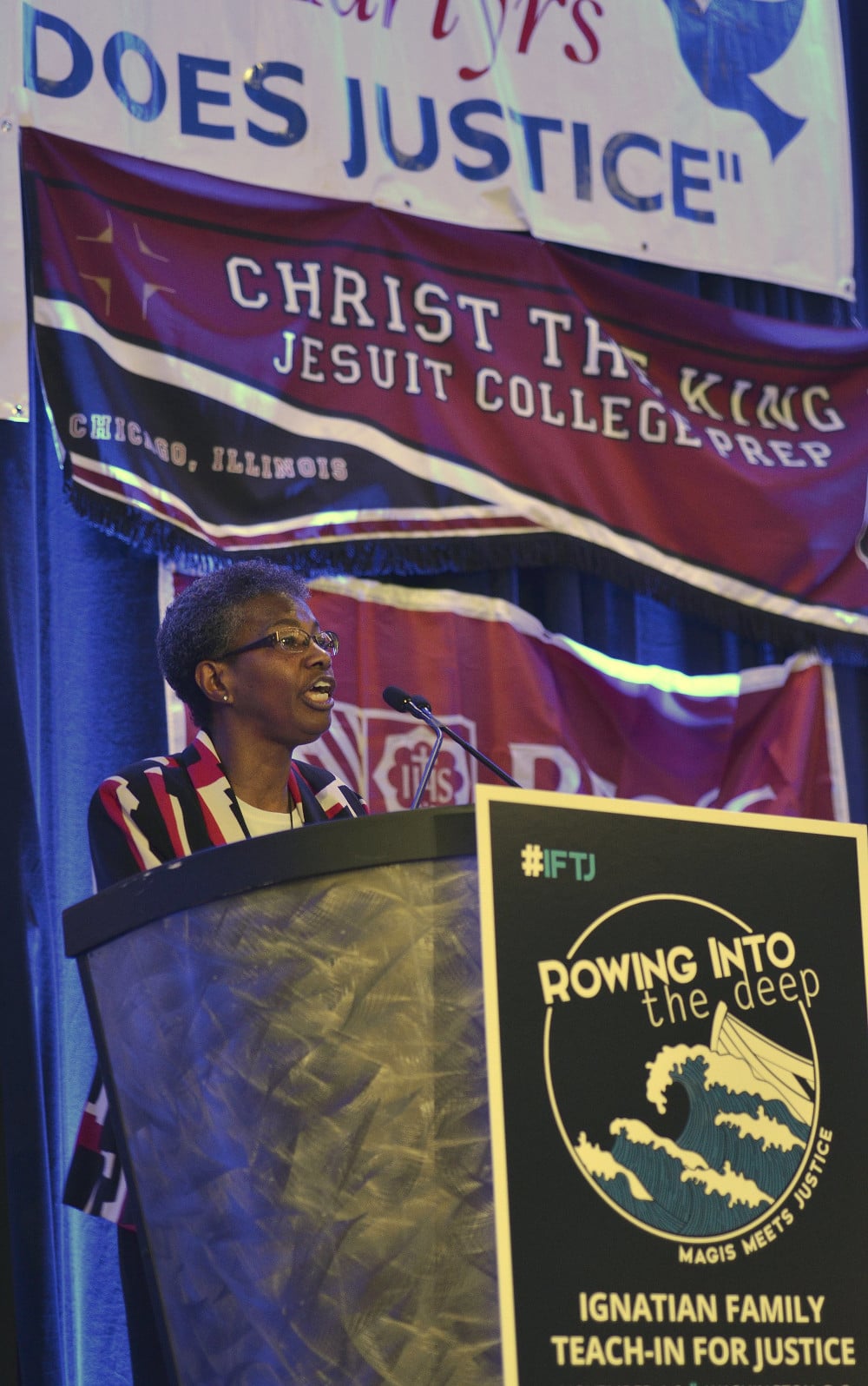

Wanting peace by working for justice « is a hard road to walk, my brothers and sisters, » Sr. Patricia Chappell told attendees at the 2023 Catholic Social Ministry Gathering in Washington in the opening plenary session Jan. 28.

« We can no longer claim to be innocent bystanders, » said Chappell, a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur, who is a longtime educator and a former executive director of Pax Christi USA. Catholics must address the systems in this country and in the church that « have kept injustice, racism and hatred alive, » and instead replace them « with the values of the Gospel and Catholic social teaching, » she said in a reflection that laid out today’s challenges for social justice ministry.

« If we want to really understand » the injustices and institutional racism of this nation’s social and political systems — put in place by « white Western European males » to maintain power and benefit themselves, « we must listen to those on the periphery who have experienced the most violence and most institutional failures, » she said. « We have to listen to those voices and listening is the key. We must listen not to refute or debate or negate (or) deny others’ lived experience. »

As she opened her talk, Chappell, who is African American, said there « will be times during this reflection you may say ‘Amen’ but other times, my brothers and sisters you may want to say, ‘Ouch.' »

« It’s OK if you don’t invite me back again, » she added with a smile, which prompted laughter from the audience. More than a few « Amens » from her listeners punctuated her remarks.

Chappell, a former president of the National Black Sisters’ Conference, is a longtime educator who has worked on issues of social justice and racism for many years. She currently is moderator of the leadership team for her religious community’s U.S. East-West province, and has served as co-coordinator of the community’s anti-racism team.

« Every single social system in this country was intentionally set up to maintain the power and privilege of the white dominant groups, » she said.

Chappell also called for an end to « silo thinking, » because all justice issues are connected.

« Is immigration/refugee reform more important than climate control? Is food insecurity more important than voting rights for all people? Is the death penalty/solitary confinement more important than the nuclear threat? Is domestic violence and abuse more important than gun violence? Is DACA more important than those with physical and mental health challenges? » she asked.

She encouraged those at the Catholic Social Ministry Gathering to see the common thread running through all these issues as they attended the meeting’s many workshops on their agenda focusing on poverty, immigration, racism, prison ministry, worker rights, criminal justice reform, mental health, economic development and other topics.

She also asked them to be mindful of these connections when they talked with their representatives on Capitol Hill the last afternoon of the Jan. 28-31 gathering.

Chappell said it « is not a coincidence » that thousands of people « held hostage at our southern border, » those seeking asylum, and those being trafficked for sexual and economic purposes are all « from communities of color. » The « staggering disproportionate number of Black and brown human beings incarcerated in this country, » she said, also « is not a coincidence. »

« Victims of infrastructure failures are found in poor white, brown and Black communities, » she said.

She pointed to water system failures: in 2014, drinking water in the city of Flint, Michigan, was found to be contaminated, exposing tens of thousands of residents to dangerous levels of lead and bacteria. It took two years or more to address, and it is still not totally resolved.

In August 2022, a major water treatment plant in Jackson, Mississippi, failed due to flooding of a nearby river but the plant was years overdue for major repairs. As a result, 180,000 residents had no running water for days, and according to a Jan. 30 FOX News report, repairs could take 10 years and drinking water availability might be intermittent. In September 2022, Baltimore became the latest major city to experience a water crisis involving contamination in the water supply.

« White supremacy is embedded in our country — and our church. Segregation and exclusion are a real part of our religious tradition, » Chappell said, noting that at one time Catholic schools would not enroll children of color, and Catholic churches often made Black Americans sit at the back of church and go to the end of the line to receive Holy Communion.

« The church was among the largest slaveholders, » she added.

In recent years, Catholic institutions have begun to address their role in slavery and the legacies of enslavement and segregation, like Jesuit-run Georgetown University in Washington with its reparations and reconciliation program for descendants of Black men and women enslaved by the Jesuits.

« We have been called to do the work of justice and peace in our own moment in history, » Chappell said.

« Who said we have to do all of this? Jesus, » she continued. « Jesus said, ‘I came so that all may have life and have it in abundance.’ Emphasis on that ‘all people’ may have life and abundance — not just the wealthy, not just a few, not just white folks, but all of us. »

The principles of Catholic social teaching were laid out in 1891, she noted, referring to Pope Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical « Rerum Novarum » (« On Capital and Labor »), which is considered the church’s breakthrough model on social teaching.

« It says regardless of race, sex, age, national origin, sexual orientation, religion, employment or economic status — all are worthy of respect. Even those brothers and sisters we may feel are offensive — they are worthy of respect, » she said.

Yet, she said, it seems few Catholics seem to know about this Catholic social teaching; and, she added, it is rarely preached from the pulpit.

The challenges for social justice work may seem daunting, Chappell said, but « we must do what we can. »