The social media landscape doesn’t lend itself well to the practice of humility. At the height of its influence in the 20th century, the legacy press landscape also traded in the inflation of egos. Yet Catholic authors sometimes said or did things that pierced that bubble of ego — and often in jarring ways. At the height of their literary success, authors like Evelyn Waugh, Muriel Spark, Graham Greene and Flannery O’Connor reflected on themselves as sinners in need of grace.

Evelyn Waugh

Waugh’s first marriage collapsed in 1929. This crisis left its mark on his satirical 1930 novel Vile Bodies, which he wrote as his own life unraveled. A year after his divorce, he was received into the Catholic Church. His conversion was an unsentimental affair. In Waugh’s estimation, the Catholic Church held the fullness of the truth, therefore it was reasonable to revere it — and that was that.

When Waugh (1903-1966) appeared in a 1960 BBC television interview, he told reporter John Freeman that in the late 1920s he was « as near an atheist as one could be. » Freeman asked Waugh to speak of the greatest gift he’d received from Catholicism. Was it tranquility or perhaps peace of mind? « It isn’t a lucky dip that you get something out of, » Waugh responded. « It’s simply admitting the existence of God or dependence on God or contact with God — the fact that everything good in the world depends on him. It isn’t a sort of added amenity of the welfare state that you say, ‘Well, to all this, having made a good income, now I’ll have a little icing on top of religion.’ It’s the essence of the whole thing. »

Waugh’s temperament was sometimes as extraordinary as his writing. He was often a cruel curmudgeon, a prickly snob; he dabbled in fascistic politics and he was mercurial. If there’s truth to the trope of upper-class British fathers preferring their pet dogs over their children, Waugh took pains to embody that truth. He wasn’t much better with adults. When novelist and friend Nancy Mitford introduced Waugh to her publisher in 1950, Waugh shocked them with his rude behavior. « How can you behave so badly — and you a Catholic, » Mitford exclaimed. « You have no idea how much nastier I would be if I was not a Catholic, » Waugh responded. « Without supernatural aid I would hardly be a human being. »

Waugh is funny in both his literature and his letters. In his fiction, humor serves to make the harsh truths of a fallen world more bearable. There’s also humor in how he recognizes his own fallen nature. That humor, however, doesn’t dull the knife that cuts away at everything that veils sin. In his 1934 novel A Handful of Dust, that veil is made of fame, privilege, power, class and socialite culture. Waugh tears the veil away in a scene that can’t be forgotten. A mother who pursues a romantic affair with an awful man called John — who bears the same name as her young son — receives news that « John » had suffered a terrible accident. As it slowly dawns on her that the victim is her little boy and not her lover, her initial reaction is to thank God in relief — before bursting into tears. The horrible scene is compelling because it’s so authentically human.

Muriel Spark

Muriel Spark (1918-2006), a generation younger than Waugh, enjoyed his support. Spark’s conversion to Catholicism in 1954 made her sympathetic, as did the fact that her own writings were also funny, cruel and engaged with faith. Her 1959 novel Memento Mori explores a community of elderly Londoners subject to cryptic phone calls. A man rings to remind them that they must die. The anonymous caller is politely stating a fact of life. Most of the victims react with indignation or paranoia. A retired penal reform activist demands that the culprit be found and flogged.

Only one character takes the call in stride. Charmian Piper is Catholic and senile. She enjoys a moment of visionary clarity when she receives the call. She tells the caller that reflecting on her death is an exercise she’s done for decades. Here’s a memorable fictional character who, in a world where self-importance and personal survival dominate, attributes less import to her earthly existence.

Spark’s father was Jewish, her mother was Anglican and she attended a Presbyterian school. Like Waugh, her conversion to Catholicism wasn’t emotional. She began reading the works of Cardinal John Henry Newman and, as she shared in a television interview, she « just drifted into » Catholicism.

« Largely I’m still a Catholic, because I can’t believe in anything else, » she said. « I’d often like to, but I can’t.” The interviewer asked her if she was satisfied with her religion. « No, » she said, smiling. « Perhaps the truth isn’t satisfying. » Spark certainly wasn’t satisfied with the church’s views on birth control — which she supported staunchly. Spark speaks of subjecting her will to examination in light of a truth that is greater than herself — even when it’s unsatisfying to do so and even if it doesn’t transform her views.

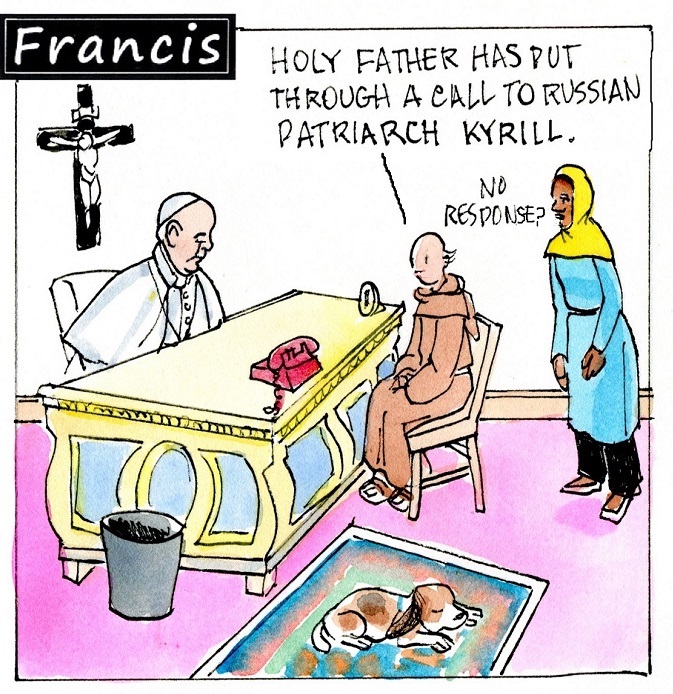

Graham Greene

In the vanguard of British authors who converted to Catholicism also stood Greene (1904-1991), the author of The Power and the Glory. In 1953, Greene got himself chastised in a pastoral letter from the Holy Office, the predecessor of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He was admonished for engaging in « odd and paradoxical » writing and for « troubling the spirit of calm that should prevail in a Christian. »

In that sense, he wasn’t any different from Waugh, Spark or — across the Atlantic — Flannery O’Connor. Greene’s protagonist was a nameless, indigent priest seeking to escape persecution and death during anti-Catholic purges in Mexico. It takes special skill to create such a memorable character without even giving him a name. The priest was a drinker, he had broken the vow of celibacy and struggled to forgive his enemies. Yet moral failure was the vehicle through which he traveled toward humility and grace.

Advertisement

The protagonist reflects on his life as a young priest: « What an unbearable creature he must have been in those days — and yet in those days he had been comparatively innocent … Then, in his innocence, he had felt no love for anyone: now in his corruption he had learnt.”

Every author, to varying degrees, writes fiction based on personal experience. When creating the « whisky priest » of The Power and the Glory, Greene was no exception. Greene was a thoughtful and tortured Catholic, a serial and selfish adulterer engaged in colorful sexual escapades, eventually a Catholic agnostic who avoided Communion for three decades and a man dealing with mental illness. Few authors struggled to map out and comprehend grace as persistently as he did.

Flannery O’Connor

O’Connor (1925-1964) was among the few. Burdened by a debilitating illness, tending to peacocks on her family farm and writing for diocesan publications, O’Connor embraced what is sometimes called a « mean grace. » She did, after all, publish a short story, « A Good Man is Hard to Find, » in which a grandmother and her entire family are brutally massacred by escaped convicts. The grandmother, a hypocrite, talks the Christian talk, but only embraces a Christ-like love for the man about to kill her in the moment before she is murdered. « She would have been a good woman…if it had been someone there to shoot her every minute of her life » — some of the most haunting words in the literary canon.

But it’s another character, Ruby Turpin from « Revelation, » a story written months before O’Connor’s death, where the author’s search for grace is most striking. Mrs. Turpin, a self-satisfied middle-class bigot of the highest order, faces the vision of a God who makes the poor and the scorned become the first and the « decent » ones of the middle class the last. Mrs. Turpin embodied the racist and classist impulses of the American south in the decades of racial segregation — impulses that ran deep and far.

O’Connor must have come across many Mrs. Turpins in her day. And to what degree did she see herself reflected in the character she had created — fallen and facing grace that was hard to bear? On May 20, 1964, in her last weeks of life, she wrote to her friend and playwright Maryat Lee about checking into Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta for transfusions and treatment. On the threshold of death, she signed one of her last letters as « Mrs. Turpin. »

These 20th century Catholic authors often wrote with striking cruelty, but also with bravery. They took a scalpel to the satiny fabrics of society, while never forgetting that they were part of that society, too.